“It was on the sixth of March, 1836, on a beautiful

Sabbath morning at the close of the first week of the month, in the loveliest springtime in Texas, that the Alamo fell. In order to get an intelligent and appreciative understanding of the situation the exercise of a little retrospection is required.

When the battle of the Alamo occurred there were

but a few thousand people in all that vast domain embraced within the geographical limits of Texas.

Louisiana was still but a province, St. Louis but a

trading post. There was no Chicago. The iron horse

had not yet disturbed the slumbers and reveries of the residents of the numerous peaceful valleys of the United States. The telegraph was unknown. There was no Kansas, no Nebraska, no Dakota, no state of California.

…The nearest settlement worthy the name was two hundred miles from San Antonio. The country was one vast area of prairie and chaparral, the home of the Indian and buffalo, the cayote and cougar. The Alamo was the strongest fortress in the territory, San Antonio the central post of military operations. It being the strongest of them all any help that might come would have to come from weaker stations.

The city was so isolated that it was a kingdom in

itself. The traveler would ride day after day without seeing a habitation of any kind, a ranch, a jackal

(“hacal”) or even a dugout, coming upon San Antonio and its mission settlements out of the depths of the mesquite, a city of the valley and plains, hidden in the mighty pecan and cottonwoods of the river, isolated and alone.

In the stone church of the Franciscans were grouped a hundred and seventy-seven courageous American pioneers. Outside were five thousand Mexican soldiers under a tyrannical leader, seeking to break down the protecting barriers of stone and mortar and massacre them all. From the tablet of memory the present geography and substantial cities and towns and railroads and enterprises of the United States and the great Southwest must be effaced.

Only the Alamo, the little town west of the river,

the handful of American defenders and the gaudily-dressed and well-equipped Mexican army without the walls, form the picture upon which the sun rose on that beautiful Sabbath in the Texas springtime, when nature was arrayed in her best garb and the soft air was laden with the delicious perfume of a thousand flowers, the birds warbling their sweet melodies in the leafy bowers of the majestic trees, and the oncoming light of the rising orb of day dispelling the mists of the valley.

It was the hour when the monks would have been

at prayer.

The siege had dragged its weary length along partly because Santa Anna had waited for reinforcements. He had learned by the experience of his generals in the field that the Texans were desperate fighters, and that nothing but overwhelming numbers could overcome them. He already had nearly five thousand men, but he waited for the arrival of an additional force of two thousand more, under command of General Tolza, before beginning his final attack upon the garrison and church. Tolza arrived on the 3d of March, and now an army of seven thousand Mexicans surrounded the Alamo.

On the 5th the commander-in-chief communicated

his plans to his generals. Unusual quantities of ammunition were distributed to the troops, and scaling ladders and crowbars were parceled out as a part of the equipment. During the night of the 5th the troops were assigned their positions and were marched to their respective stands. The Matamoras Battalion was halted on a favorable position near the river. Behind the Alamo General Cos occupied a commanding station with two thousand well-trained troops, among them those he had led out of the mission when the Americans came into its possession, General Tolza’s command holding the ground to the south. The attacking troops were under Amat, but Santa Anna was the power behind

them all….

Within the Alamo the gallant little band of Americans were waiting patiently for the attack they knew would come. Travis had called them all together, from church and fortress, from barracks and prison, from hospital and kitchen, and had given them his farewell address…

Then in silence and with determination they repaired to their various stations, prepared to fight to the end, to deal blow for blow, take life for life, and surrender only in the arms of death, never in the hands of the enemy. The roof of the church held their cannon. Behind its embattlement they would fight to the last. If driven from the azotea they would seek the refuge of the heavy-walled rooms, and there in hand-to-hand struggle would hold on to the death.

There were no dissenters. But one man, whose

name was Rose, preferred to try to escape, and he lowered himself beyond the rear wall, battered down in previous conflicts. History gives no record of his fate. It could not have been better than that of the patriots who preferred to stay, the surrounding limits being overrun with Mexican soldiers on the lookout for escaping Texans.

With the approach of dawn the Mexicans began

their closing in. On every side the brilliant equipment of a gaudy troop glittered in the darting streaks of the rising sun. From out the trees they came. From out the chapparal their forms rose like a mighty swell. Behind the Alamo General Cos, whom the Americans had paroled on honor, led his regiments of Montezumas directly under the walls on the East. Santa Anna came from across the river, behind the main body of the army, urging them on with all the wickedness of a demon and the skill of a trained chieftain.

As the sun rose over the hill to the East the sharp

rattle of musketry was reverberating through the bush on every side, while the heavy boom of the Mexican cannon from across the river and to the South of the fortress echoed and re-echoed down the valley and to the river’s springs. A perfect rain of shot and shell, a hail of minnie balls and musketry lead, kept sweeping the parapets of the Alamo. The Mexicans pressed on, coming closer and closer, drawing their lines tighter and tighter on every side of the fortress, the little band of Americans biding their time.

Travis and Crockett and Bonham were calm. Bowie

was below on his dying couch, violently ill with pneumonia, but from his bed he encouraged the men and calmed the women. Occasionally the sharp crack of a Texas rifle told the story of the death of a Mexican officer, the patriots reserving their fire for the commanders and until the scaling of the walls, which they knew was to come, should have been begun.

Finally this moment arrived. The Mexicans pressed

their men forward. The outer walls were attacked

with rams and cannon and were easily broken down. The enclosure outside the church swarmed…

“Boom,” “boom,” sung their cannon from parapet

and corner into the swarm below. “Crack,” “crack,”

“ping,” “ping,” sang their rifles, and before their galling fire of ball and slug a thousand Mexicans went to earth.

The Texans fought like fiends. Their carnage was

awful. Every man was an expert with his gun and

employed it to the best advantage.

As the ladders were thrown against the outer walls

of the church and barracks and Mexican heads would show themselves on the upper rounds, above the wall, “crack” would go a rifle or a pistol, and down would fall a swarthy form.

But their numbers made their losses little felt, and

under the prodding of their commander’s swords and the wild excitement of the conflict others would mount the ladders and get to the top, only to fall upon the stricken form of a comrade who had already gone the way.

The cannon were no longer of service on either side. The conflict had resolved itself into a personal encounter between man and man. The Texans shot as long as they had ammunition, and then clubbed the Mexicans down the walls, until exhausted by their struggles and laborious physical efforts they began to fall and the Mexicans saw their victory.

Over the walls they climbed and fell. With clubbed

rifles, pistol butts and knives the Americans kept up the struggle…

It was an awful carnage, a slaughter whose equal

has not been recorded since the day of Thermopylae.

Under a fierce ramming and barring the Northeast

corner of the monastery gave way, and through the

break Castrillion forced his men. The plaza was filled in a minute, the court was packed, and the North doors of the church, into which the Americans had backed for their final stand, was attacked by a tremendous power of men and rams. The openings were blocked by sacks of sand, behind which dodged the remaining patriots, picking of a man here and there with leaden balls, nails and scraps of iron, with which they were

compelled to load their guns.

The doors were blown in with powder blasts and

then, after the fearful struggle, which had now lasted more than two and a half hours, Mexican and Texan faced each other in the burying ground of the Alamo, the main body making their final stand in the auditorium of the chapel.

Again the Mexicans brought their cannon into play,

so dreadful had been the havoc the Americans wrought among them. The front doors were attacked with grape and canister, yielding at last to a terrific bombardment, which cost the Americans many a life. Into the chapel the Mexicans madly rushed, over the bodies of patriots killed by the grape and canister fire they fell. The Americans were now attacked in their final chamber of death from behind and in front, and there they fought as never men fought before, until every heart had been stilled in death and every voice had been forever hushed.

With pistol-butt and rifle, knife and bayonet, with

stones and pieces of iron, they fought their death-

fight, overwhelmed and crushed by force of numbers, no one asking for quarter, none offering it to the other.

The confusion was awful, the carnage frightful.

The crack of firearms, the shouts of defiance and

groans of pain, the death agonies of the wounded, the screaming of the women, the loud reverberation of the cannon without, fired in upon the gallant handful which were left, what an awful contrast within the sacred walls of the old Franciscan chapel with the service to God which was solemnized on the Sabbath of the monks and their converts!

Down into the very jaws of death climbed the Mexicans who scaled those walls and swarmed the yards, and into the jaws of death madly rushed the soldier who dared his way to the chapel. It cost a life to enter a room, even the bedridden Bowie fighting from his couch and yielding only when he fell back upon his pillow with his life shot out.

History tells that Travis was killed early in action

and that Crockett, Evans and Bonham directed the

fighting as long as further directing was to be done. Under a dying injunction from the leader Captain Evans tried to blow up the magazine at the final moment, that he and his compatriots might perish by their own act and not by the hand of the invader, but as he was touching the light to the fuse he fell, pierced to the heart by a Mexican bullet, and the carnage went on.

Crockett was among the last to die. His “Betsy”

made many a Mexican rue the day he had joined the army, and when there was no more time to load he clubbed many a foe to death with his gun before he finally succumbed, his body bullet-ridden for minutes before he gave up the struggle.

It was well along toward the middle of the forenoon

before the conflict ended. The Americans had fought against insurmountable odds, and had held out against an enemy of tremendous strength, vicious cunning and revengeful head and heart. Every inch of ground had been contested. For every Texan’s life the Mexicans had paid thirteen fold….

The siege and battle of the Alamo caused intense excitement throughout the country and aroused the interest of the United States in the cause of Texas. Officially the great republic did not interfere. But individually thousands of her citizens hurried to the frontier and took up arms with the Texans, excited to action by the courage and fortitude of the heroes of the Alamo, whose immolation made Texas free.”

From Historical sketch and guide to the Alamo

by Leonora Bennet published in 1904

https://archive.org/details/historicalsketch00bennett/page/60

Source says not in copyright

Image: The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Picture Collection, The New York Public Library. “Battle of the Alamo.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47e0-f7a6-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

Susanna Dickinson, one of the few on the side of the Texians, who survived the siege of the Alamo.

Image via Wikimedia Commons, public domain

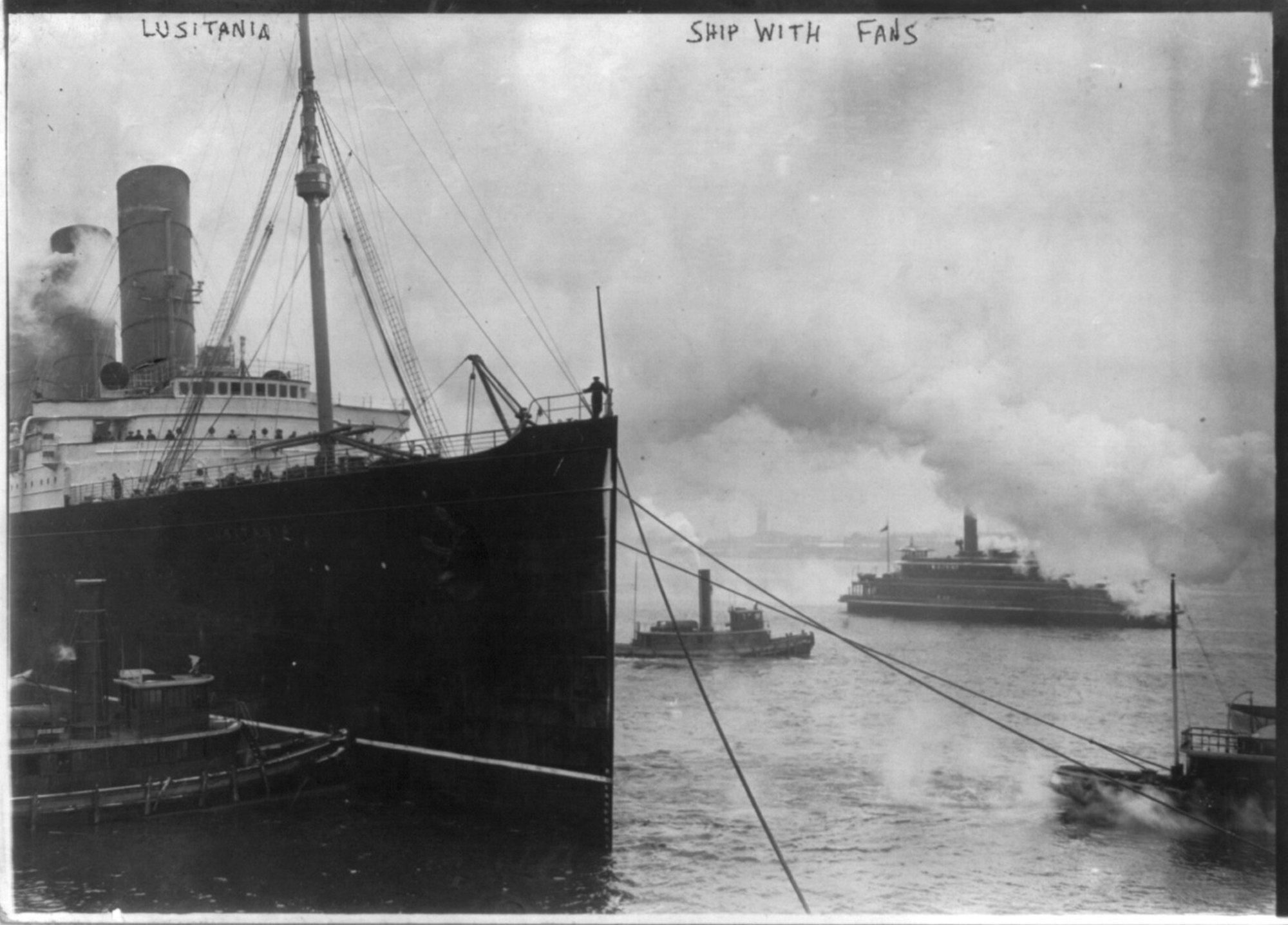

LUSITANIA, New York City: view of bow with tugs, March 6, 1914

Image via Wikimedia Commons, public domain

Born March 6, 1905 in Kosse, Texas Bob Wills – the King of Western Swing – was a singer, songwriter, fiddler, and bandleader. That’s Bob (front, center) with his Texas Playboys on tour. When asked in 1957 about rock-n-roll he replied “Why man, that’s the same kind of music we’ve been playin’ since 1928!”

Image via Wikimedia Commons, no known copyright, public domain in the US.

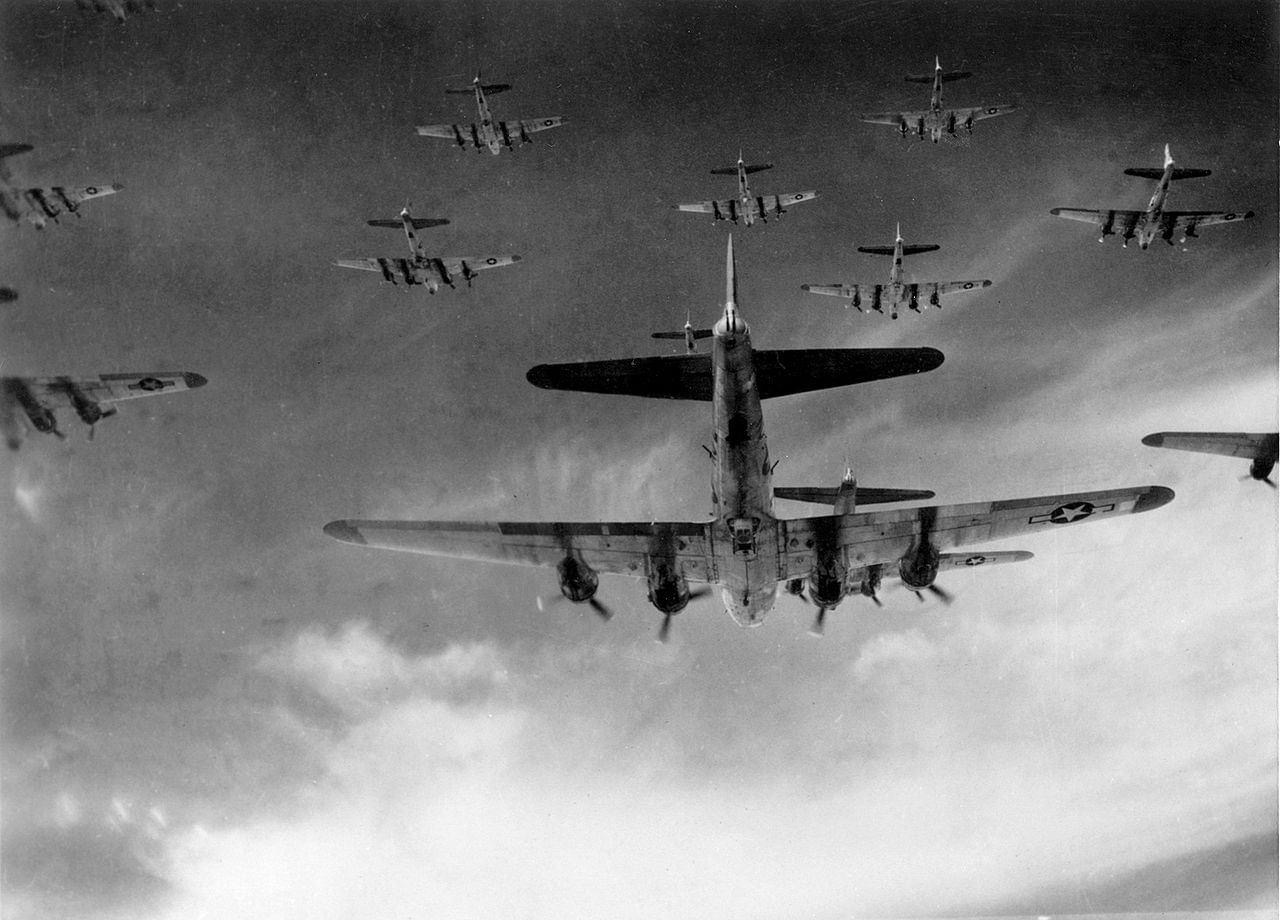

On March 6, 1944, the United States conducted a major daylight bombing raid over Berlin.

Hundreds of American bombers (about 700) including B-17 Flying Fortresses dropped numerous bombs on the defiant city. Nearly 10% of those bombers that flew in the raid were lost.

During WWII, Allied forces dropped over 1 million tons of explosives over Germany.

Image: Group of B-17 Flying Fortress bombers via Wikimedia Commons, public domain

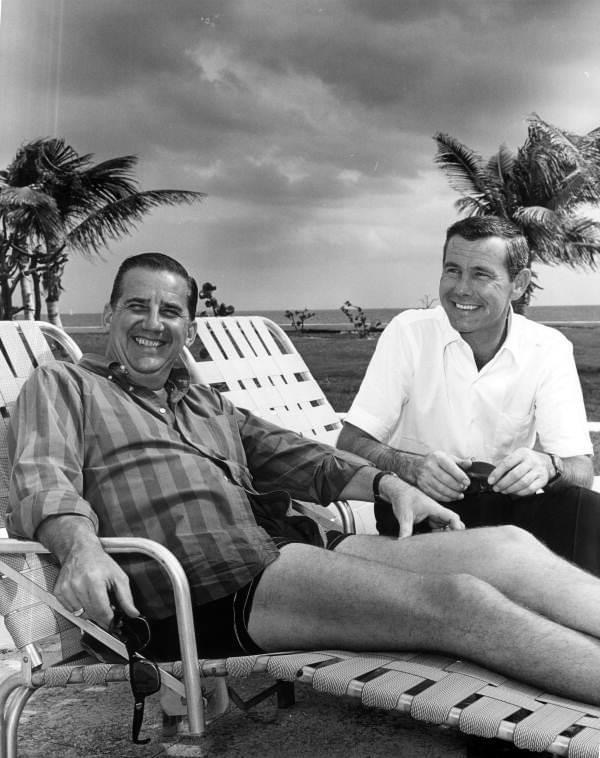

On March 6, 1923, U.S. Marine Veteran and Tonight Show sidekick, Ed McMahon, was born in Detroit, Michigan

Image of Ed McMahon and Johnny Carson in the 1960s

via Wikimedia Commons, no known restrictions

Comedians Bud Abbott and Lou Costello in the NBC radio studios in 1942.

Lou Costello was born on March 6, 1906 in Paterson, New Jersey.

Image via Wikimedia Commons, public domain

Crowds gathered at Harvard University on March 6, 1902 which was the day when Prince Henry of Prussia received an honorary doctorate (LL.D.) from Harvard during his visit to the United States.

Image via Wikimedia Commons, public domain

On March 6, 1921, the top-grossing film of that year, “The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse” was released.

Image: Publicity photo of Rudolph Valentino from “The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse” in 1921 via Wikimedia Commons, public domain

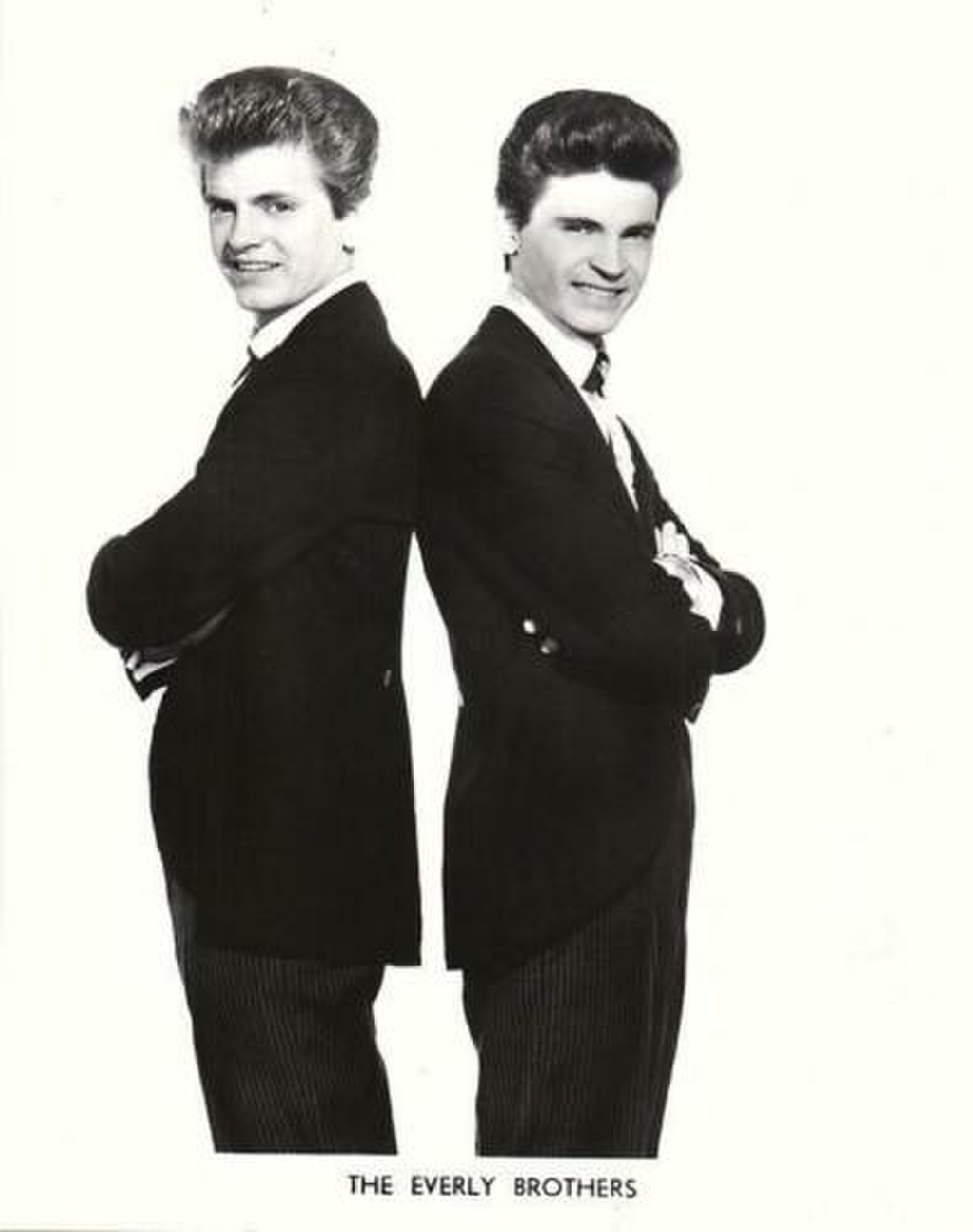

In just two takes the Everly Brothers recorded their hit song “All I Have to Do Is Dream” on March 6, 1958

Image via Wikimedia Commons, public domain

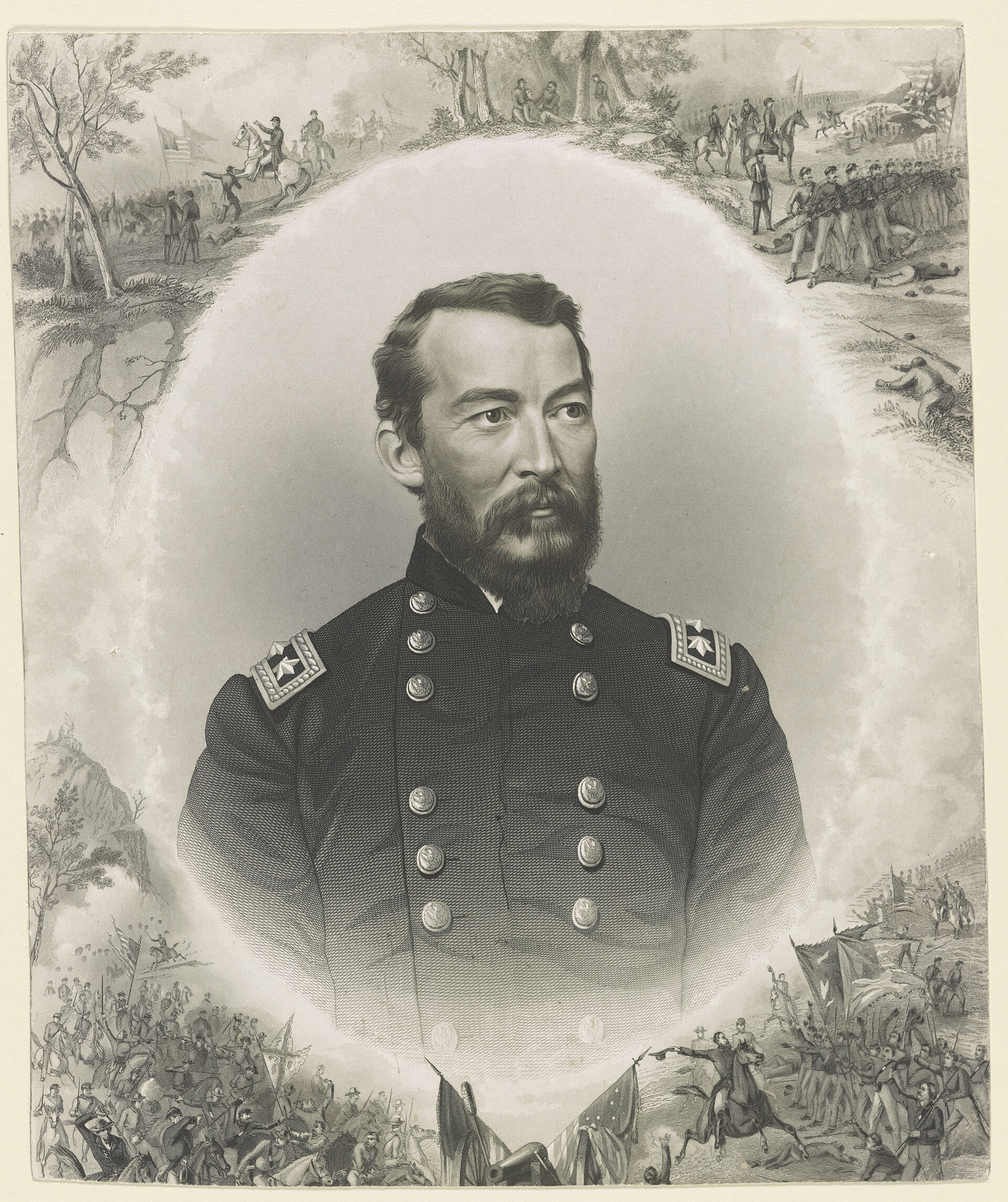

General of The Army, Philip Sheridan, was born on March 6, 1831 in Albany, New York.

During the Great Chicago Fire of 1871, Sheridan was in Chicago at the time. He coordinated relief efforts during the tragedy, and because of this, he and his wife were later gifted a home in Washington, D.C., by the citizens of Chicago.

Image via Wikimedia Commons, public domain

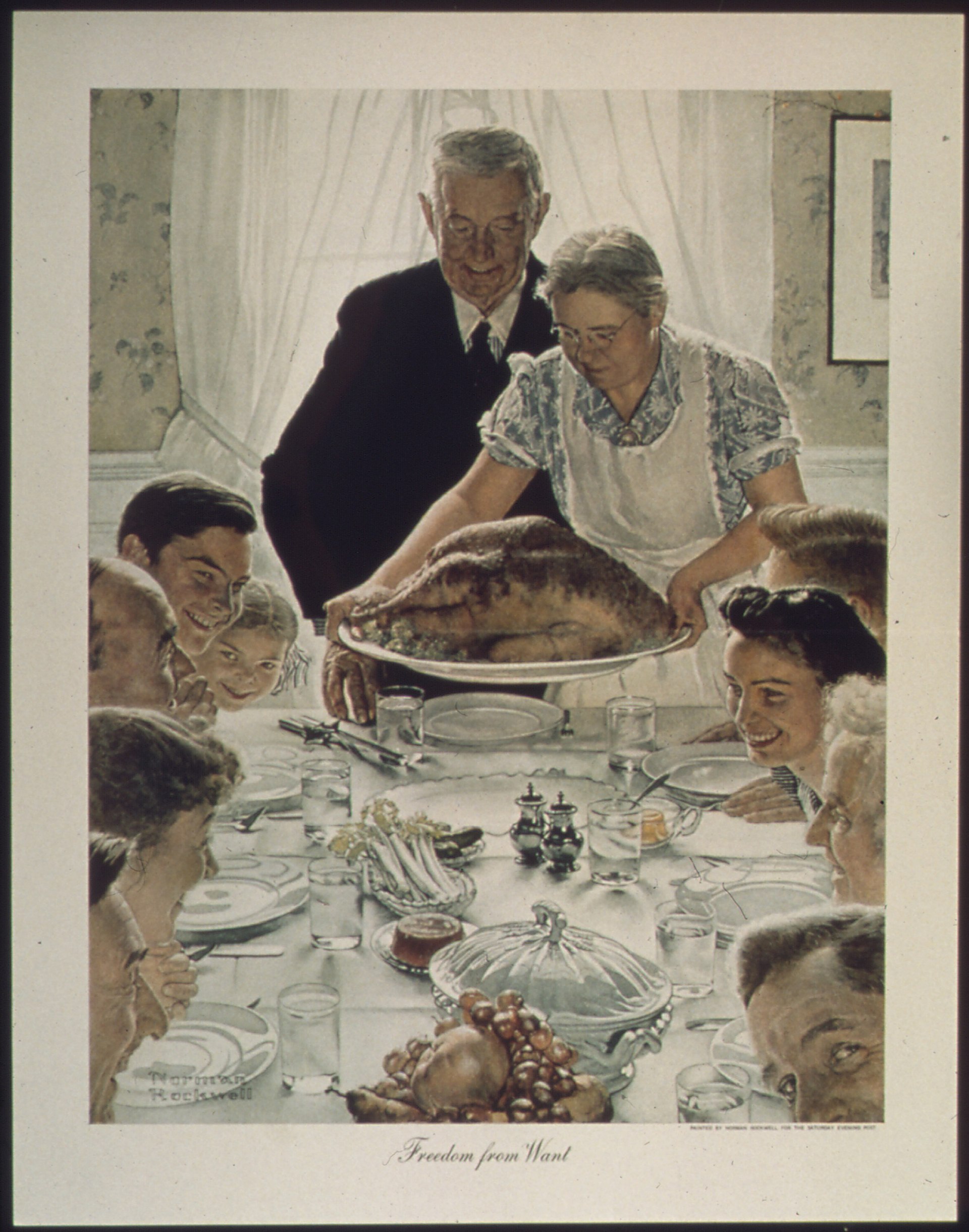

On March 6, 1943 “Freedom from Want,” the famous painting by Norman Rockwell, was published in the Saturday Evening Post.

Image via Wikimedia Commons, public domain in the US.

Group photo of more than 100 members of the Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce during their excursion to Pomona, California on March 6, 1903

Image via Wikimedia Commons, public domain in the US.

A look down Pike Street toward the Manhattan Bridge in New York.

March 6, 1936

Image via NYPL, public domain

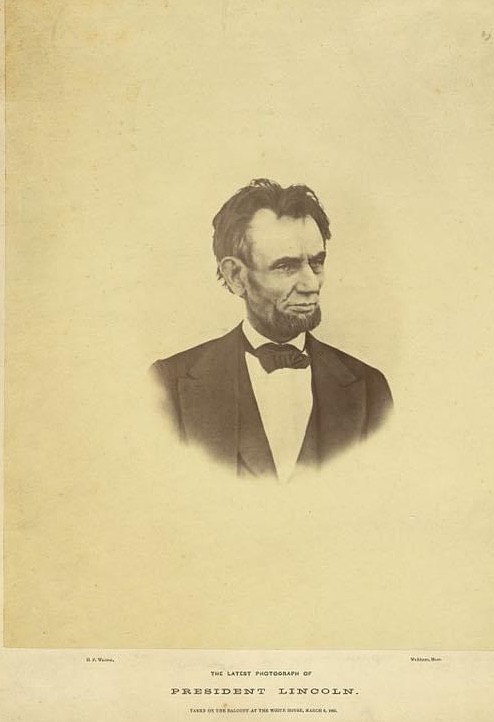

“The latest photograph of President Lincoln – taken on the balcony at the White House, March 6, 1865”

via Library of Congress, no known restrictions

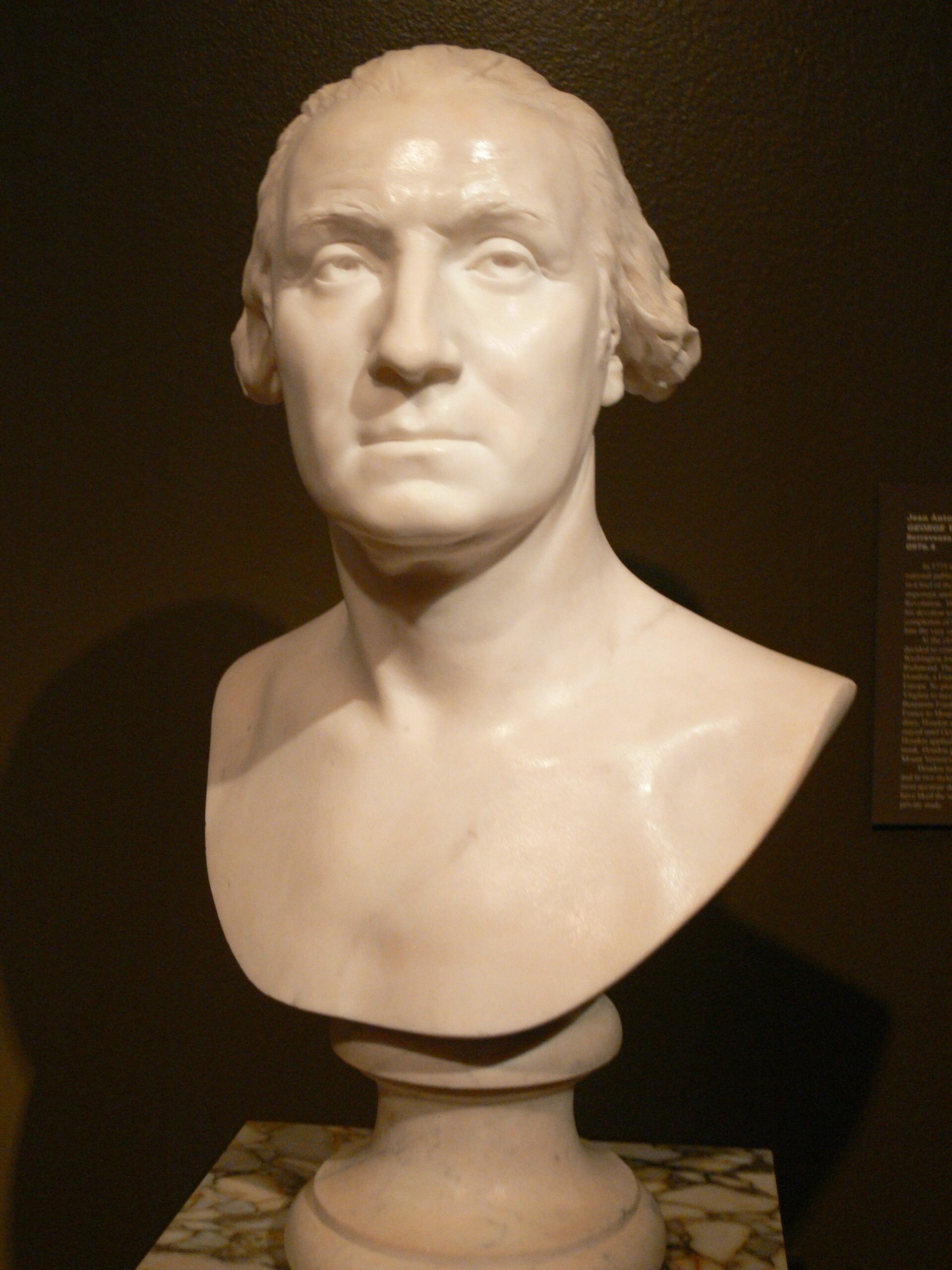

“But we must, like other States engaged in the like glorious Struggle, contend with Difficulties. By Perseverance, and the Blessing of God, I trust, if we continue to deserve Freedom, we shall be enabled to overcome them. To that Being, in whose Hands is the Fate of Nations, I recommend you, and the Army under your Command.”

John Hancock to George Washington in a letter dated March 6, 1776

Image: Bust of George Washington from 1786 by French sculptor Jean-Antoine Houdon, photo from Wolfgang Sauber via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 3.0