In the lush, dark jungles of the Southwest Pacific, where maps were scarce and about as useful as toilet paper and silence was the key to survival, a small band of American Soldiers worked their way through the dense vegetation, carefully approaching their objectives. They wore no unit insignia, received little recognition, and most of the time, no one paid them any attention. However, their covert reconnaissance, hostage rescuing, and ability to coordinate with fledgling guerrilla forces dramatically changed the course of the War in The Pacific. This unit was relatively unknown and largely forgotten except by their families and other U.S. Special Operations Forces (SOF). They were the Alamo Scouts — an elite organization sanctioned by Lt. Gen. Walter Krueger’s Sixth Army—whose history, accomplishments, and legacy remain one of the quietest heroic stories in American military history.

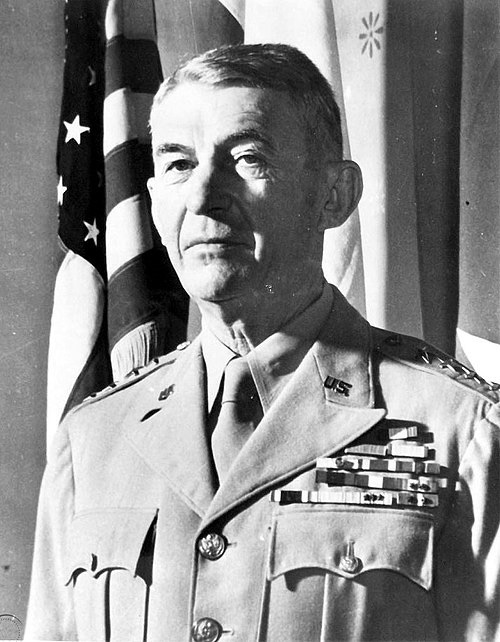

By late 1943, Allied forces faced a dilemma: how to gather reliable intelligence in terrain that swallowed radio signals and defied aerial surveillance. Krueger, assigned to lead the Sixth Army (publicly known as “Alamo Force”), recognized the need for a new type of soldier: one trained not for combat, but for invisibility. On November 28, 1943, Krueger signed the order to establish the Alamo Scouts Training Center near Kalo Kalo on Fergusson Island, New Guinea.”

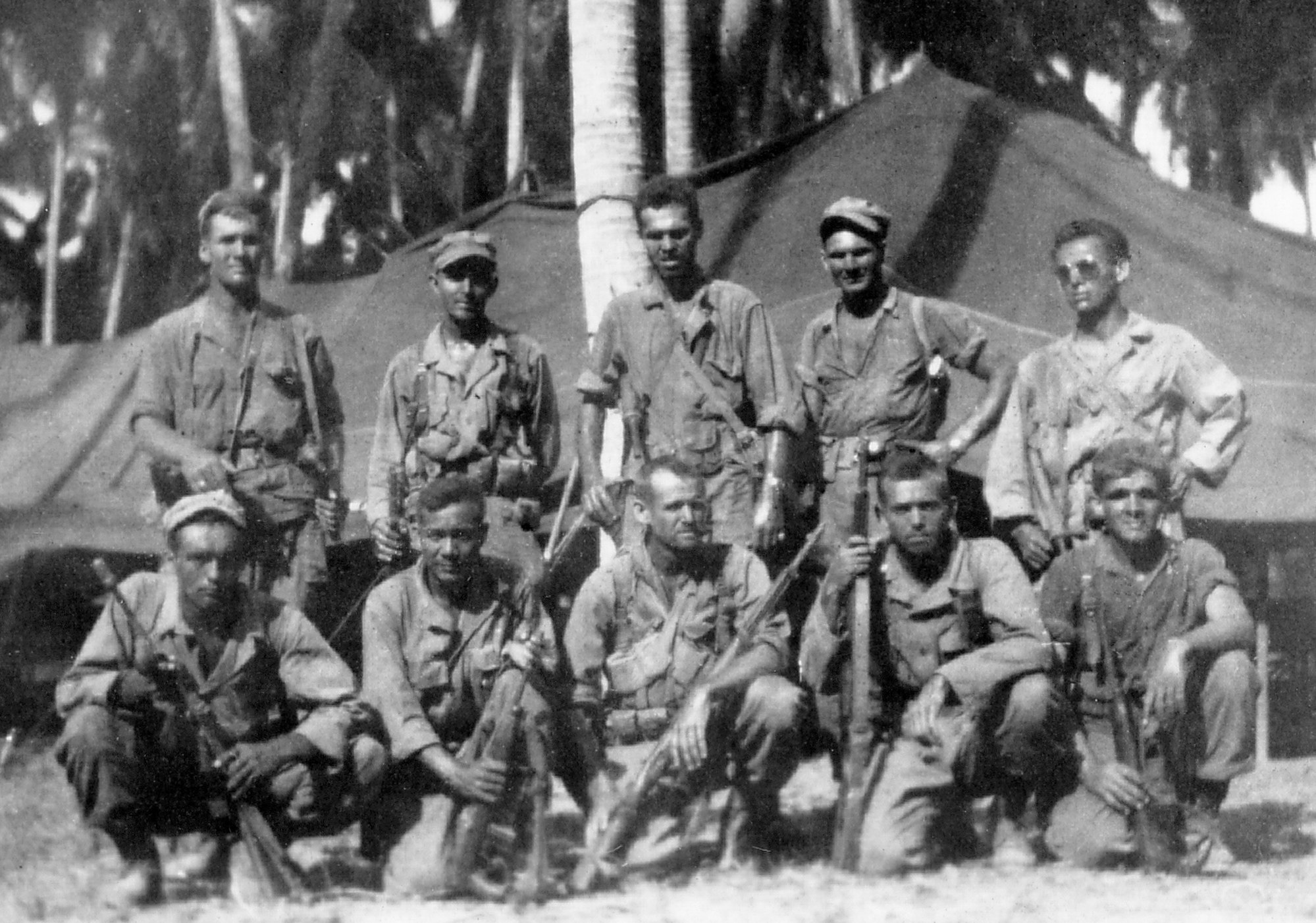

The Alamo Scouts were not like other special units in so far as they were not raised on bravado. The Alamo Scouts were precision tools designed to observe not to contact. Deployed ahead of the invading forces, they endeavored to document territory, identify enemy troop strength and rescue anyone who may have been left behind. The six-week crucible involved preparation for jungle warfare, air and sea insertion from rubber boats, PT boats, and submarines, and rigorous intelligence reporting. From a pool of more than 700 volunteers, only 138 individuals were selected.

Training included navigation, weapons, communication, and physical conditioning. Scouts needed to know how to travel undetected, observe and not be observed, and survive behind enemy lines for more than a week. Most missions involved co-operation with Filipino guerrillas, relying on their local knowledge and courage. Scouts learned how to wear the clothes of a local, using as little gear as possible and placing great trust in each other and the civilians who risked everything to assist them.

via Alamy

Staff Sgt. William “Bill” Nellist, led a reconnaissance mission near Cabanatuan in January 1945. His team had confirmed the location of a Japanese POW camp in Luzon, the defenses in place, and provided the intelligence that facilitated one of the boldest rescues of the war. He did not speak of Cabanatuan again. He noted, “We did what we were trained to do.” His humility reflected the ethos of a unit with emphasis on precise completion of task as opposed to praise.

The Cabanatuan mission, conducted with the 6th Ranger Battalion and Filipino guerrillas, freed more than 500 Allied prisoners with minimal loss of life. It remains one of the most successful rescue missions in modern history. The Scouts’ contribution to the operation was largely absent from the official record of the Cabanatuan mission. Many details of the mission were classified for decades, and the impact of completing this historically significant mission was buried in the bureaucracy of Special Operations.

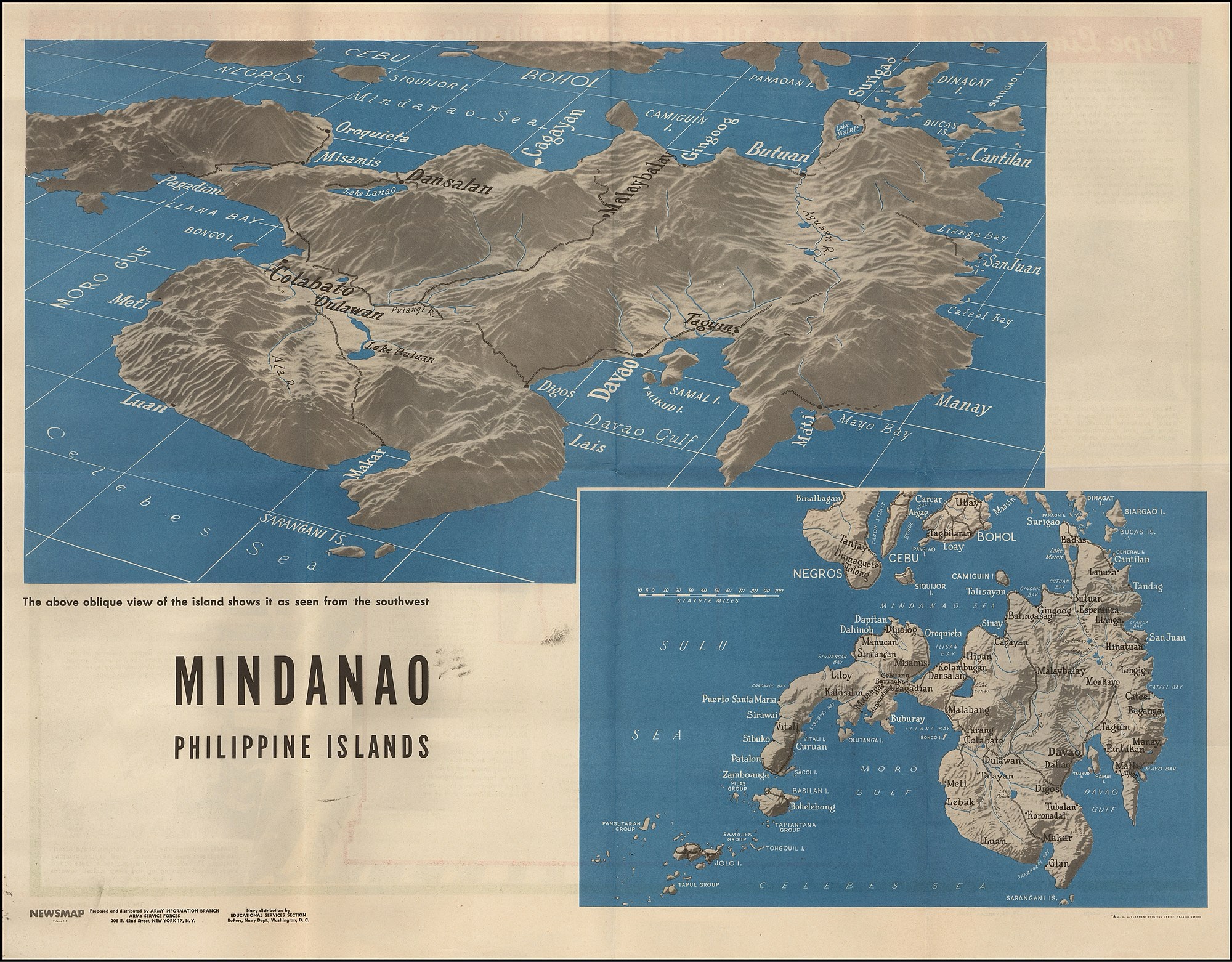

In mid-1944, a Scout team was tasked with observing a Japanese airfield on Mindanao. En route, they arrived at a village devastated by occupation. Abandoning their original mission, the team chose instead to assist the villagers—burying the dead and documenting the atrocities they encountered. The report they submitted was not tactical in nature, but it proved valuable in postwar investigations. It was a reminder that intelligence is not always strategic; sometimes, it is moral.

The Alamo Scouts disbanded in November 1945 in Kyoto, Japan. Many of the Alamo Scouts went on to serve in the newly formed Army Special Forces. The Scouts brought inclination to discretion, adaptability, and experiences related to cultural fluency in the jungles. In 1988, the Special Forces Tab formally recognized the Scouts as part of the lineage of modern special operations.

The story of the Alamo Scouts invites reflection on how military history is assembled—and how the aesthetic of war often overshadows its quieter acts of valor. The Scouts remind us that some of the most important contributions happen outside the spectacle of combat. The greatest acts of resistance often occur in silence: in accepting, in waiting, in witnessing. Each Scout carried the courage of a warrior, not the glamour of one. They operated on the margins, as part of a professional military practice that helped secure the outcome of a global conflict through stoicism, precision, and trust.

via Shutterstock

Leave a Reply