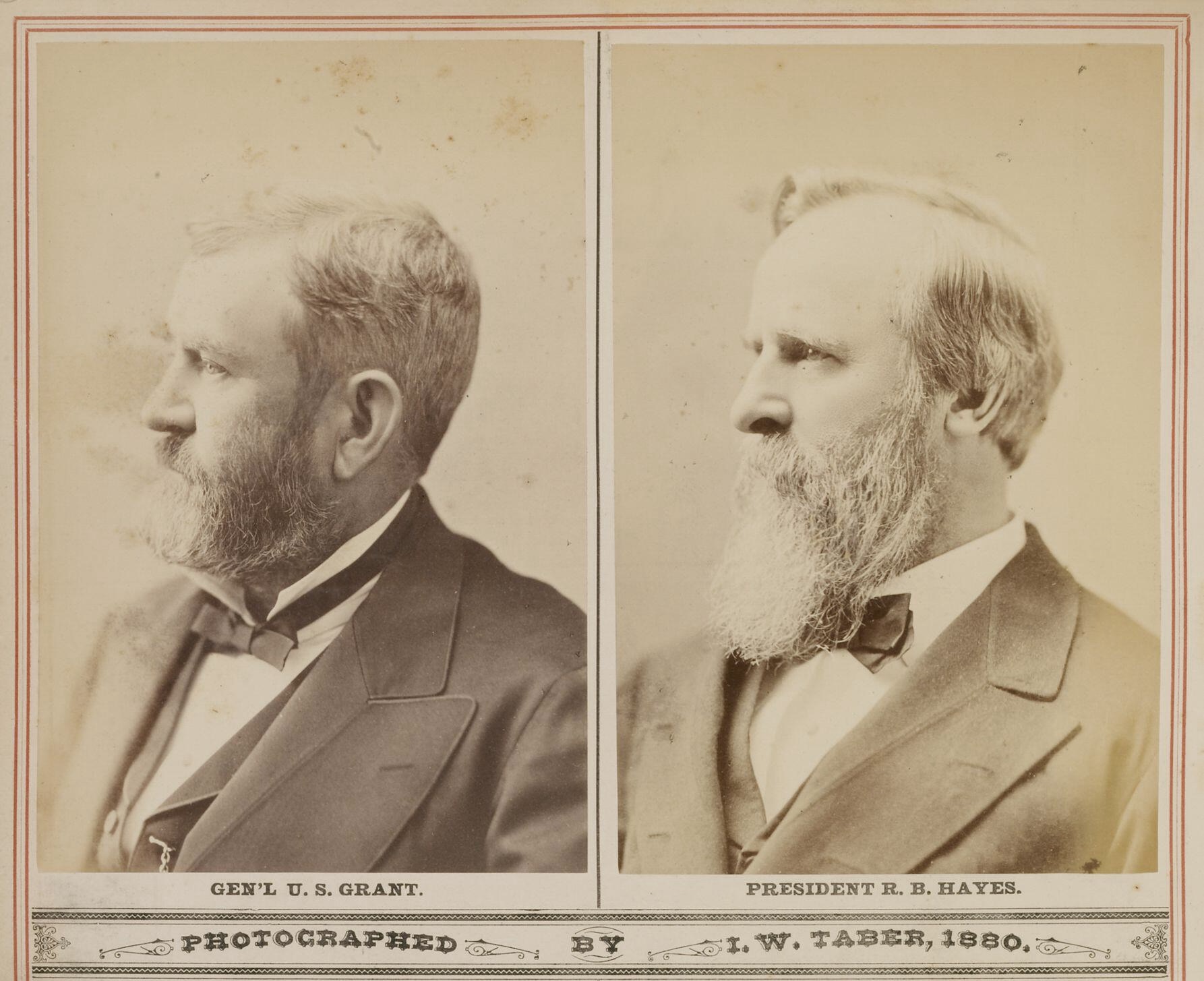

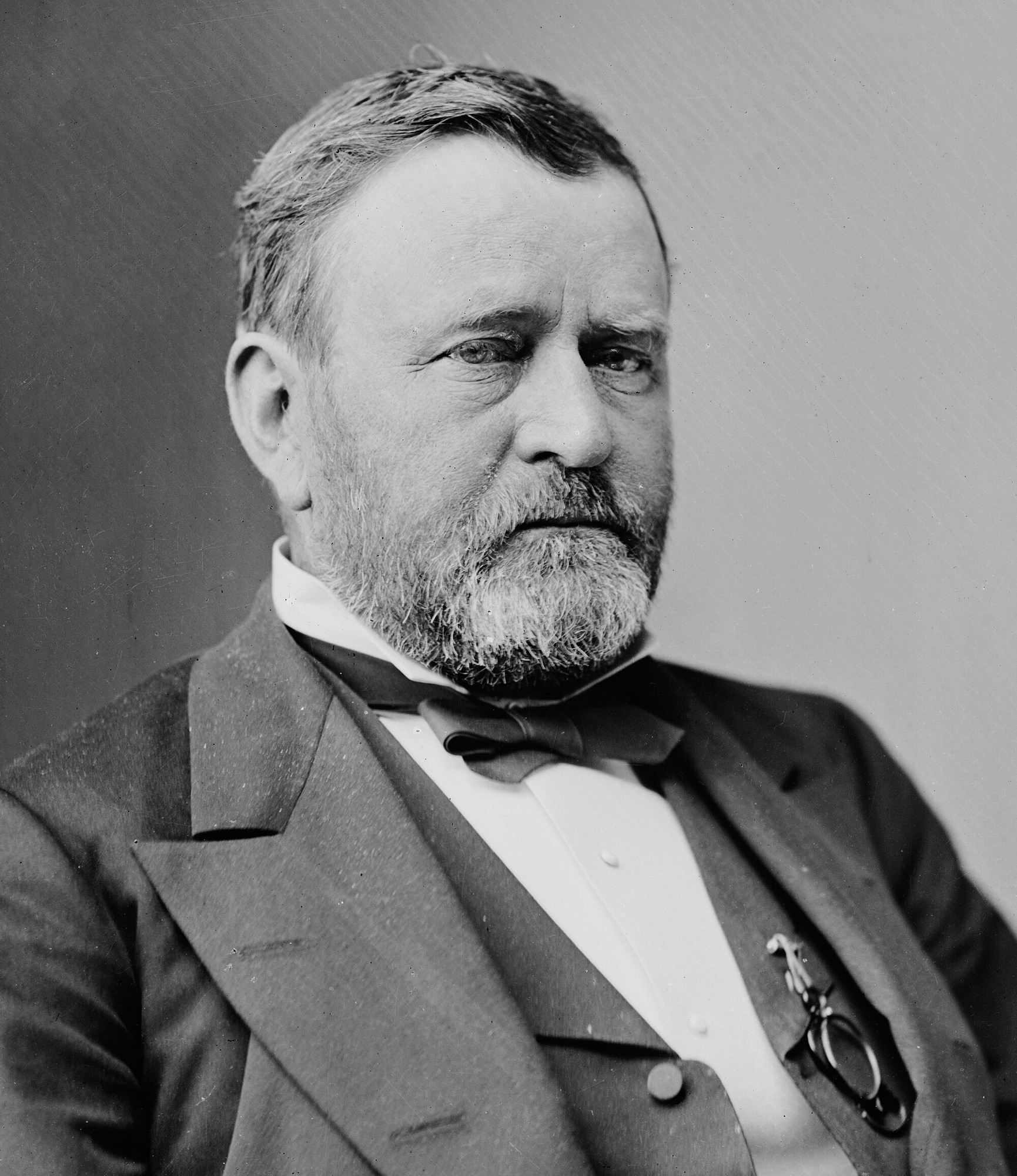

For years before any votes were tallied, Ulysses S. Grant and Rutherford B. Hayes were comrades forged by Civil War sacrifice, even as Reconstruction politics drove a wedge between them. Grant admired Hayes’s integrity but bristled when Hayes allied with the reformers who broke from Grant in 1872—an alliance Grant felt implicitly repudiated his two presidential terms.

Hayes then emerged as a genuine “dark-horse” candidate in 1876, chosen to unite rival Republican factions. That nomination only deepened their tension even as it offered a path out of party deadlock.

When contested returns from Florida, Louisiana, South Carolina, and Oregon plunged the election into chaos, Grant set aside personal grievances for the sake of the Republic. He dispatched federal troops to protect polling in Tallahassee and privately lobbied key leaders—John Sherman, James Garfield, Stanley Matthews—to uphold Hayes’s claim. In those fraught weeks, duty eclipsed annoyance, casting Grant as the reluctant kingmaker.

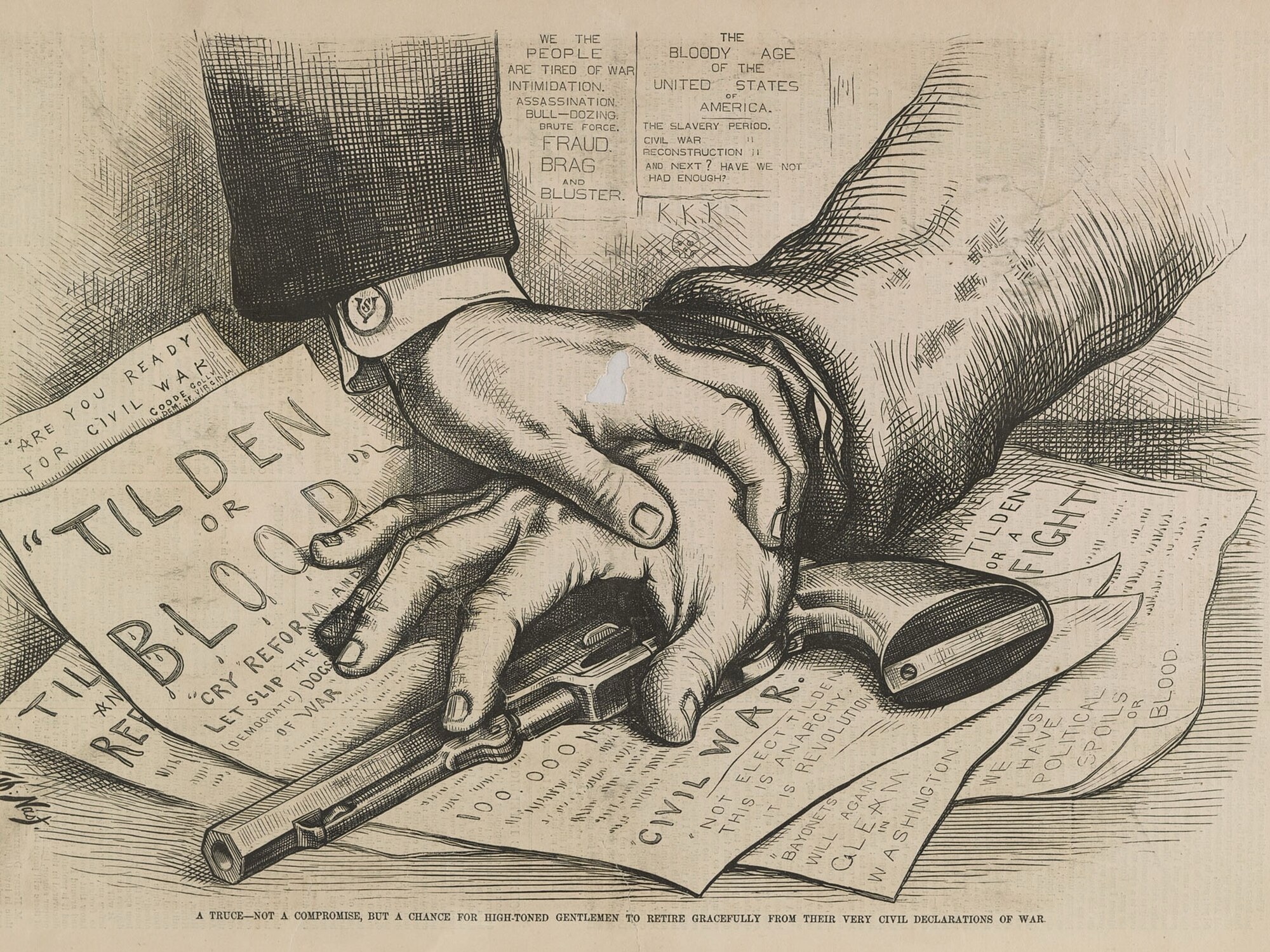

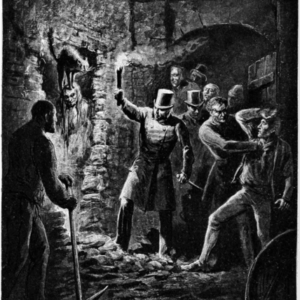

But outside the corridors of power, the nation simmered. The “TILDEN or BLOOD” cartoon, published amid the deadlock, captured the mood with brutal clarity: one hand clutches a pistol, the other a ballot, as slogans threaten civil war and invoke the ghosts of Reconstruction. The image is not subtle—it’s a warning. Americans were tired of fraud, force, and sectional strife, yet many feared the election might reignite it.

Grant understood this. His interventions weren’t just political—they were preventative. By deploying troops and quietly steering party leaders, he sought to contain not only electoral chaos but the public fury it risked unleashing. The cartoon’s restrained gun, held back from violence, mirrors Grant’s own posture: firm, reluctant, and deeply aware of the stakes. In that moment, he wasn’t just preserving Hayes’s claim—he was holding the Republic together by the wrists.

On the eve of inauguration, they met for a private dinner in the White House East Room. Grant stood and offered:

“I give you my full confidence, sir, and pledge the counsel and support of myself and my friends.”

Visibly moved, Hayes clasped Grant’s arm and replied:

“Your counsel is worth more than any political bargain. I accept it gratefully, knowing how deeply you love this Union.”

Days later, Grant sent his parting benediction to Hayes in Ohio,:

“My dear General Hayes, the presidency will soon be yours. May you wield it with wisdom and moderation, ever mindful of our reunited country’s interests.”

Hayes answered at once:

“Thank you, Mr. President. I am humbled by your confidence and hope to earn your friendship in this anxious hour.”

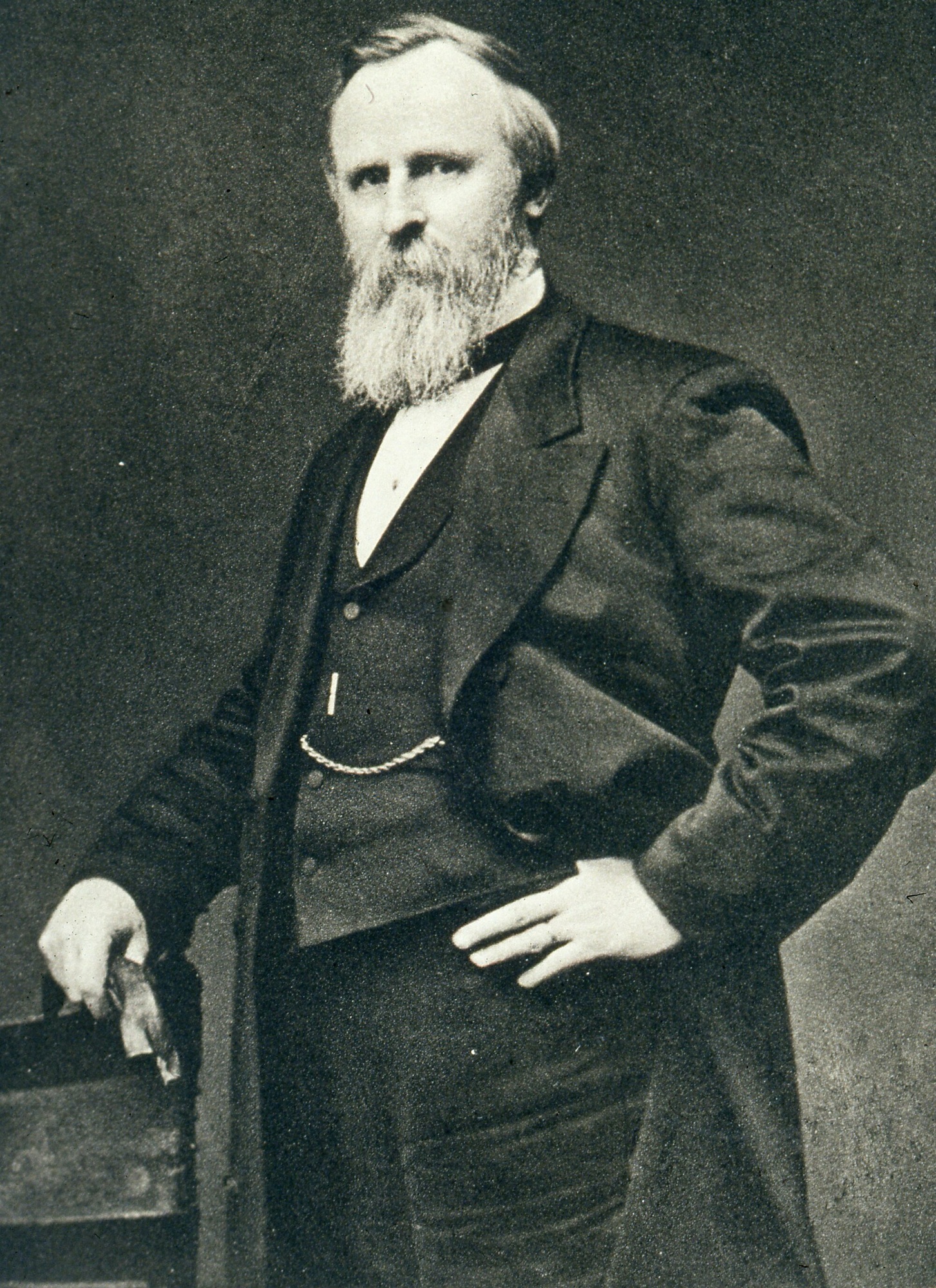

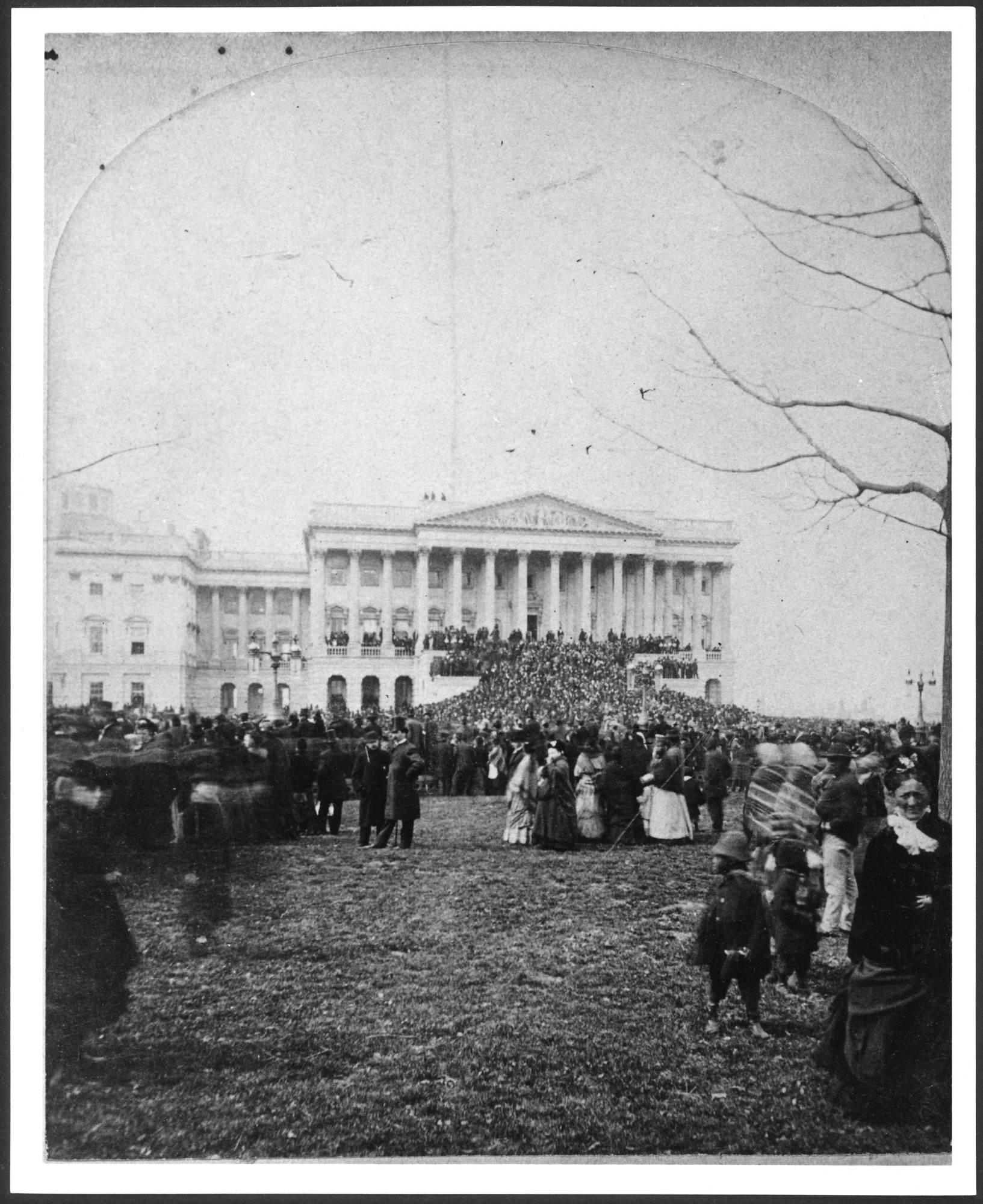

Privately sworn in on March 3 to preempt unrest and honor the Sabbath, Rutherford B. Hayes took the public oath two days later—under flags, scrutiny, and the shadow of compromise

The very next day, on the Capitol steps, Hayes addressed a still-healing nation:

“My fellow citizens, the eyes of millions are fixed on our future. Let us remember that our common interests transcend party and that we must not revive former dissensions.”

Reporters and aides noted him clutching Grant’s letter in one hand and his inaugural text in the other—a silent emblem of their shared commitment.

In the months that followed, Grant withdrew from supervising the final troop removals, leaving Hayes to implement the Compromise of 1877. That retreat imperiled the fragile gains of Reconstruction and paved the way for Jim Crow, a human cost that both men lamented in private correspondence.

Meanwhile, Hayes pressed ahead with civil-service reform and reconciliation, always valuing Grant’s statesmanship. Their letters grew more formal but never lost warmth—measured counsel, private critique, and enduring respect for a Union preserved by sword and ballot.

Note: All quoted exchanges are reconstructed from surviving letters and memoirs; exact wording is approximate.

Leave a Reply