Frederick Douglass viewed photography as a revolution in and of itself during a century dominated by steam and ink. He recognized the power of portraiture to change public perception and elevate a fugitive to a position of leadership long before social media transformed images into brands. Some claim that he was the most photographed American of the 1800s. However, these were not sittings for vanity. Douglass used daguerreotypes in particular as disruptive tools. He turned to the camera not just to be remembered but also to be seen — correctly, incisively, and honestly — against a backdrop of political erasure and minstrel caricature. This article explores five of Douglass’s most striking daguerreotypes, each of which serves as a visual representation of a chapter.

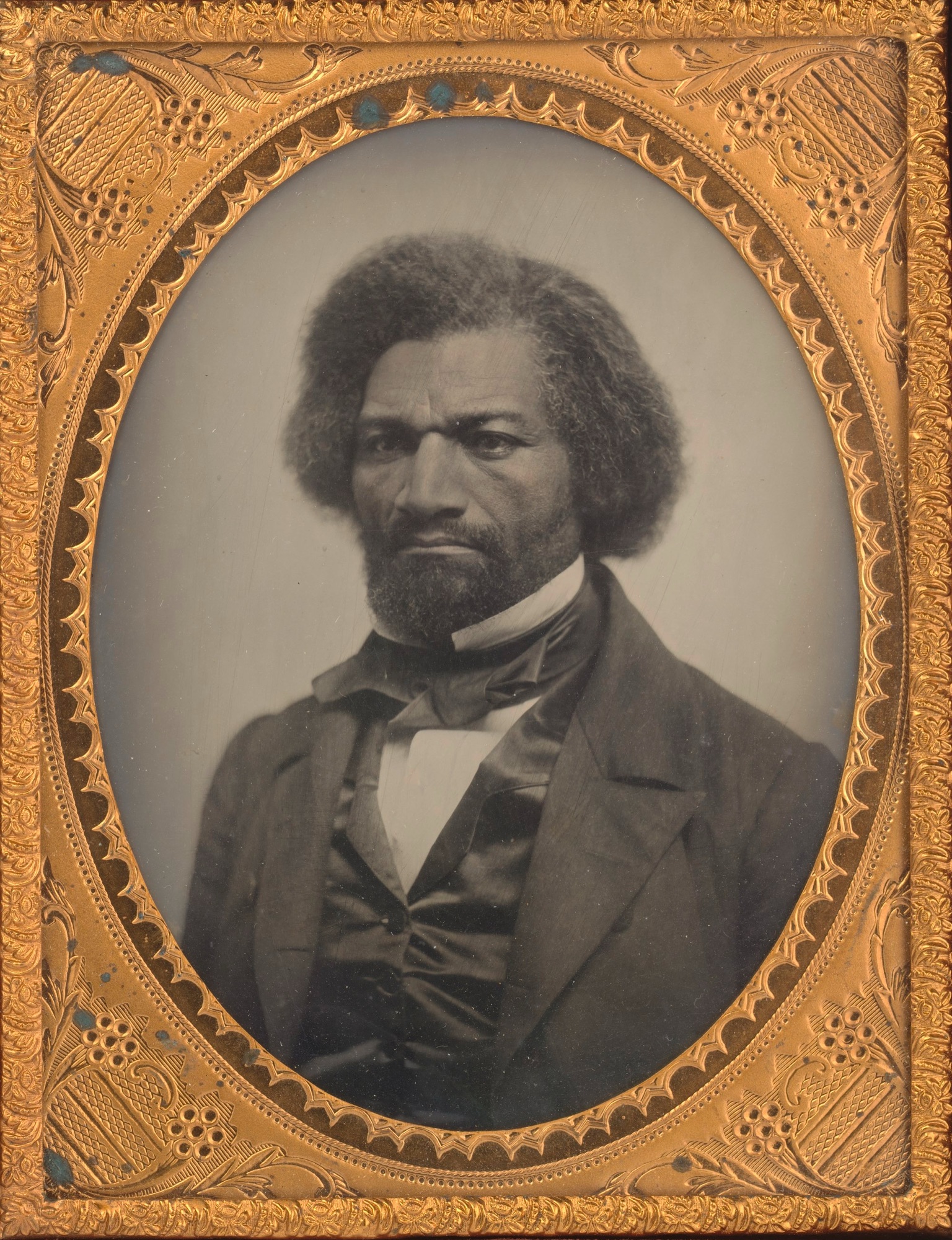

Daguerreotype of Frederick Douglass (c. 1855–1858)

This image, which was encased in velvet and gilt, was intended to last rather than be admired momentarily. Following the release of My Bondage and My Freedom, Douglass positioned himself as a cultural architect rather than just a slave survivor. A Black leader taking charge of his image in a time when such agency was rarely permitted is conveyed by the sharp suit, calm posture, and direct gaze. This portrait serves as a public strategy as well as a personal legacy.

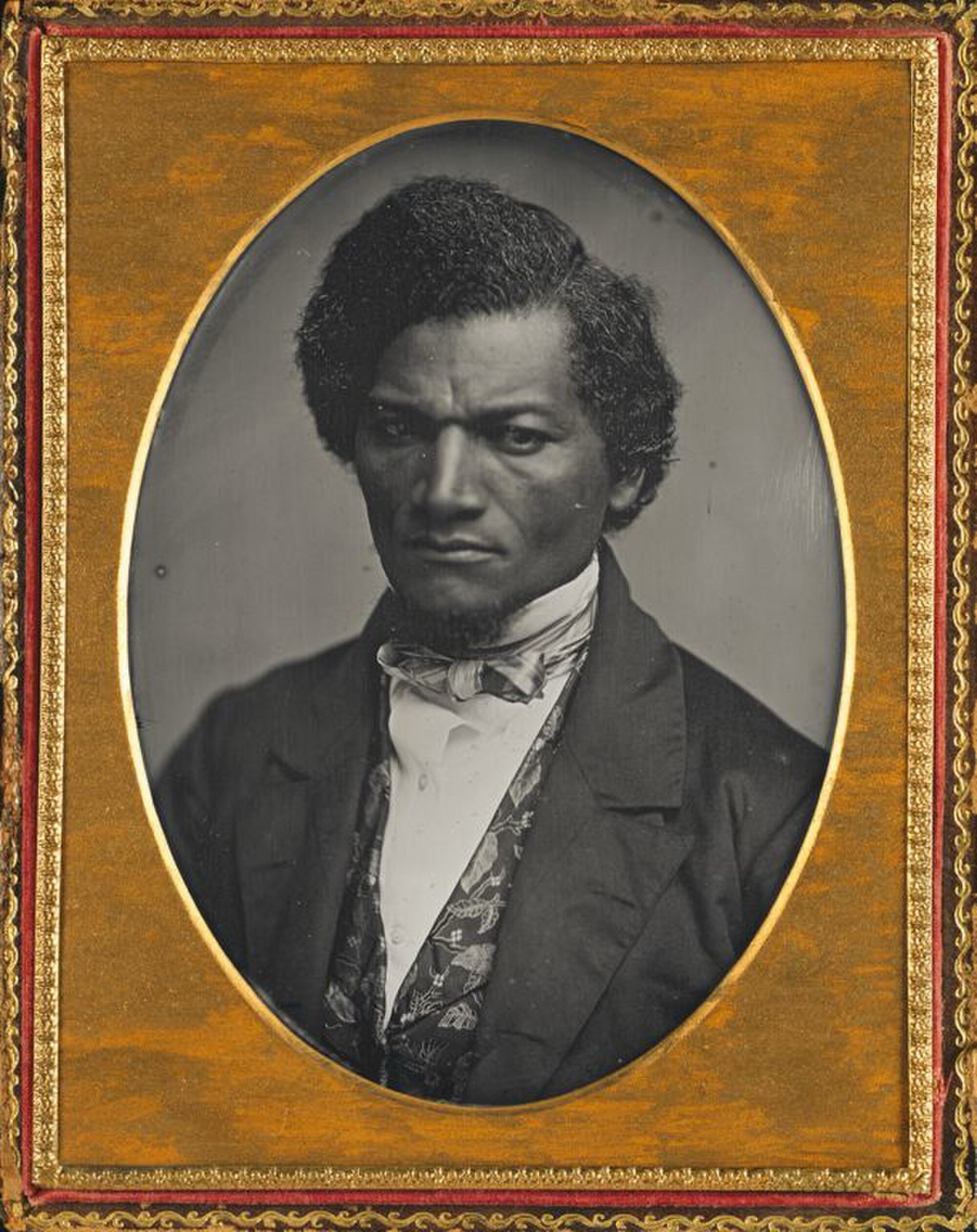

Daguerreotype of Frederick Douglass (c. 1850s)

In an era when portraiture was rare and often distorted by racist imagery, Douglass took control of the lens. This daguerreotype, encased like a relic, frames him not just as an individual, but as a statement. His polished attire, upright posture, and penetrating gaze speak to strategy — a deliberate act of self-definition. Around this time, Douglass was delivering landmark speeches and reshaping the boundaries of public discourse. The image is less about appearance and more about assertion: I am here, and I will be seen

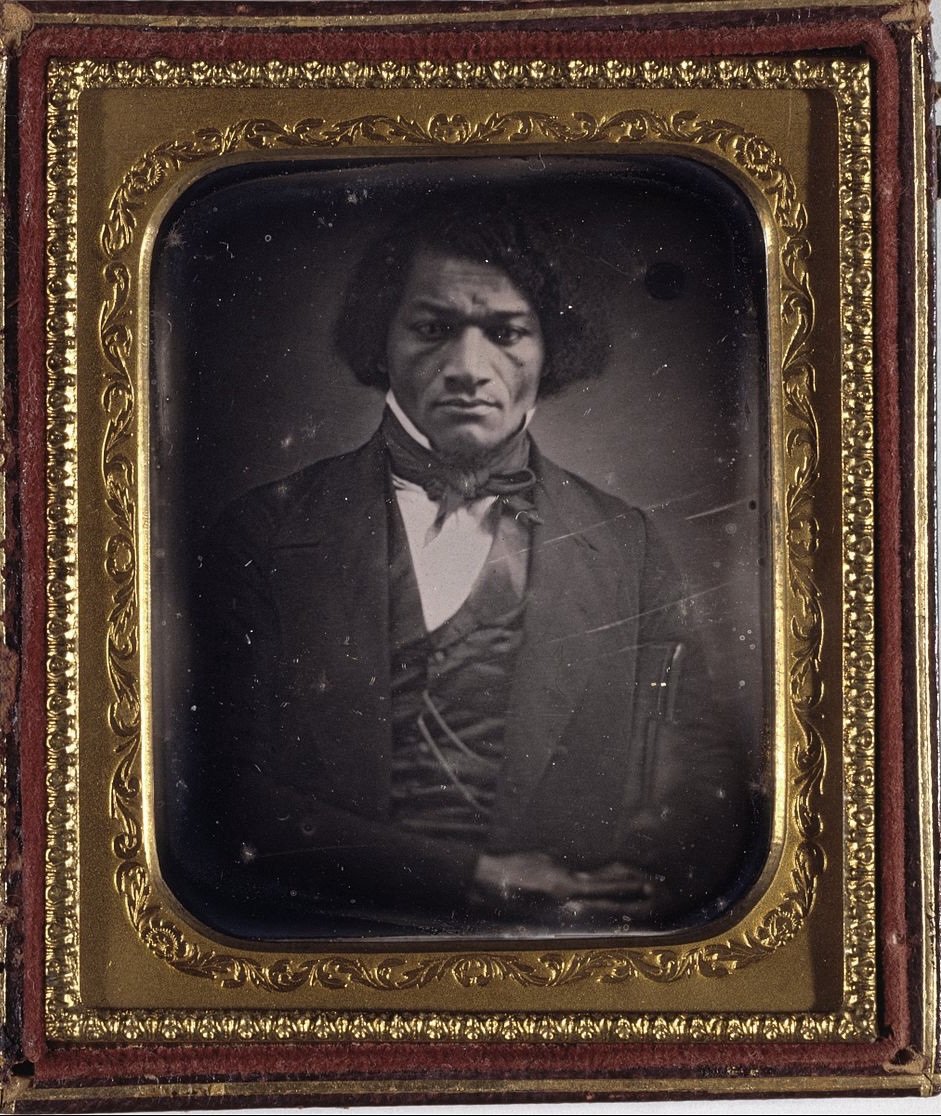

1847 Portrait by Samuel J. Miller

Taken the same year Douglass founded The North Star, this daguerreotype captures him as a self-fashioned intellectual and abolitionist firebrand. His tightly pressed lips and direct gaze challenge viewers to confront the gravity of slavery and the moral imperative to resist it. In an era when Black Americans were denied agency in both life and image, Douglass chose to sit for portraits that counteracted racist caricature and positioned him as equal — a man of ideas, dignity, and direction.

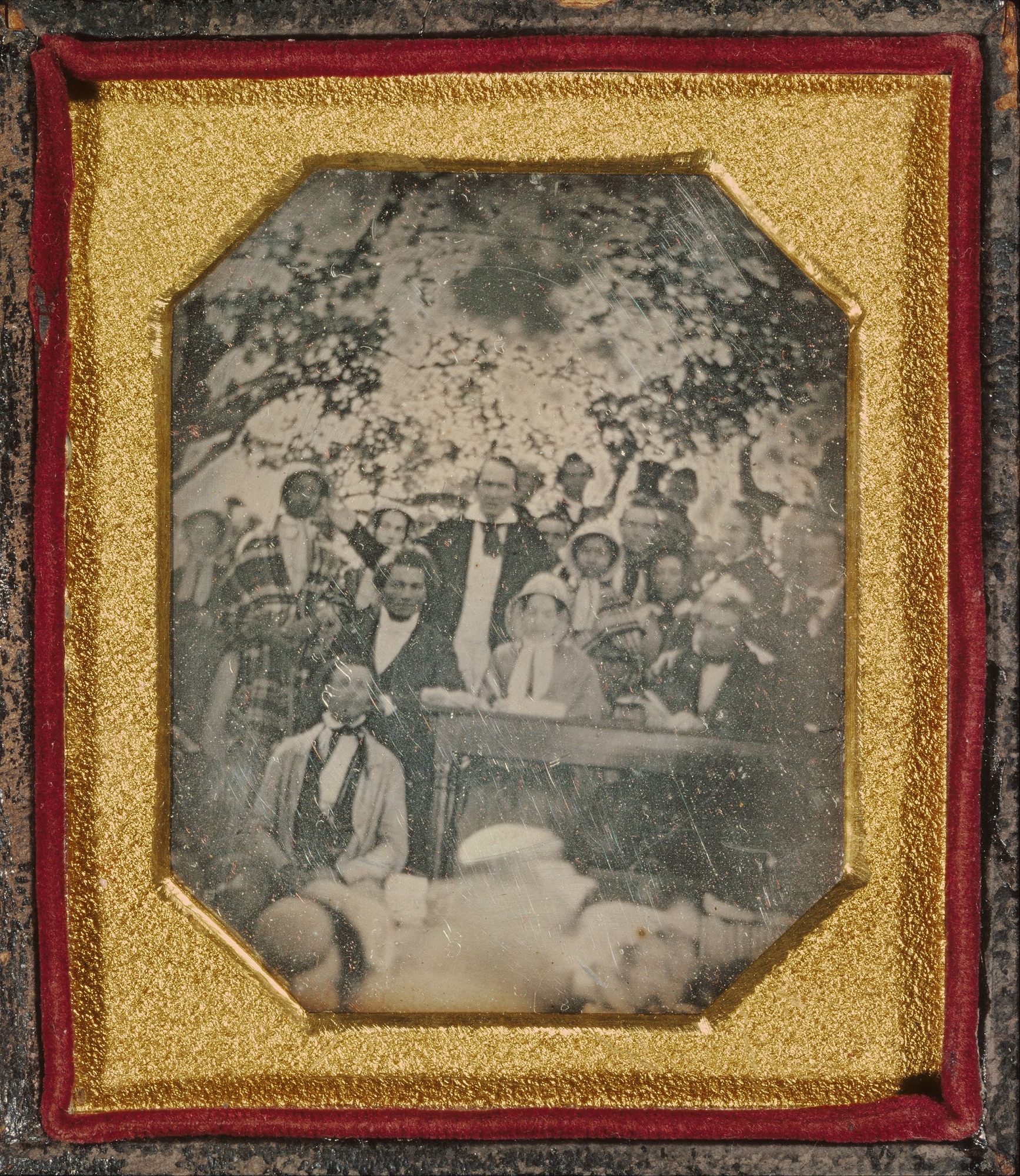

Fugitive Slave Law Convention, Cazenovia, NY (1850)

In the orchard of Grace Wilson’s school, abolitionists gathered under open skies to defy a law not yet passed but already feared. Douglass, seated at the table’s edge, presided over the largest known meeting of fugitive slaves in U.S. history. Gerrit Smith stands with arm outstretched, rallying the crowd. Days later, Congress would pass the Fugitive Slave Act — but here, in this grove, resistance was already blooming. The daguerreotype, intended for jailed abolitionist William Chaplin, became a lasting symbol of solidarity and defiance.

Daguerreotype of Frederick Douglass (c. 1852–1855)

Encased in gold and shadow, Douglass confronts the camera with the same intensity he brought to the podium. This portrait likely dates to the years when he delivered his searing indictment of American hypocrisy on Independence Day and published his second autobiography. The image is deliberate and a declaration of self-authored identity. In an age when photography was still novelty, Douglass wielded it as a tool of truth.

Frederick Douglass understood what many would not until decades later: that how one is seen — and who gets to do the seeing — shapes the boundaries of social justice. His portraits were not just likenesses; they were declarations, confrontations, and aspirations. With each daguerreotype, Douglass chipped away at the visual architecture of racism, replacing caricature with character, erasure with evidence.

It’s interesting to note that Douglass’s mother, Harriet Bailey, named him Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey. While there’s no surviving documentation confirming that he was named Augustus after the famed Roman emperor or Washington after the American founding father, both names are associated with powerful roles in leadership and shaping their respective eras.

The images in this collection span decades of activism, transformation, and profound leadership. From the piercing intensity of his early gaze to the quiet authority of his elder years, Douglass’s evolving presentation reflected not vanity, but strategy — a refusal to be misrepresented in a culture all too eager to distort. Even in group photographs like the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law Convention, his presence anchors the frame, reminding us that liberation is both personal and collective.

He once wrote, “Men are whipped oftenest who are whipped easiest.” That principle applied not just to bodies, but to perceptions — and Douglass never allowed his image to be easily subdued. These portraits endure because they are more than historical curiosities. They are cornerstones of self-authorship and resistance.

And in their silvered surfaces, we still find truth looking back.

Leave a Reply