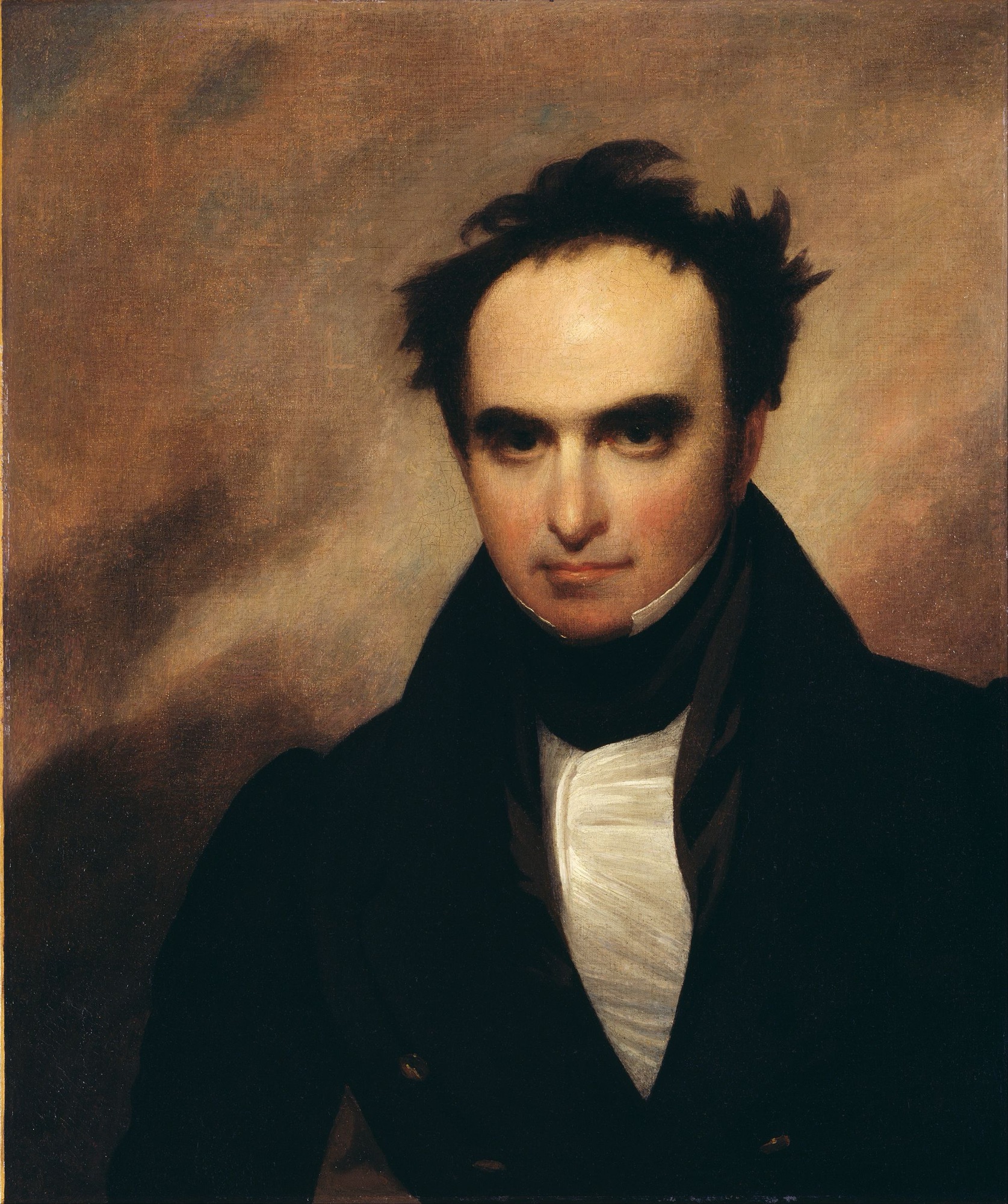

Daniel Webster was born in 1782 on the rough hill-country of Salisbury, New Hampshire, son of a Revolutionary War soldier who had a passionate belief in education. Webster was somewhat frail in health but possessed an extraordinary intellect and resolve. Eventually, he learned to overcome his childhood fears of public speaking. Subsequently, Webster became one of the most effective political orators in American history. From the time he graduated from Dartmouth College in 1801, Webster’s voice was a formidable instrument capable of thrilling crowds, stopping opponents, and establishing the language of law and nation.

Webster climbed the legal ranks rapidly. He argued and won more than two hundred cases in the U.S. Supreme Court, helping to define the nature of federal power and the breaks on constitutional interpretation. He preserved the fidelity of contracts in Dartmouth College v. Woodward, advocated for the implied powers of Congress in McCulloch v. Maryland, and claimed federal supremacy over interstate commerce in Gibbons v. Ogden. He was regarded as one of the best trial lawyers of his time; he had dead-on pauses, and he could produce a phrase with the same weight and resonance as the best scripture.

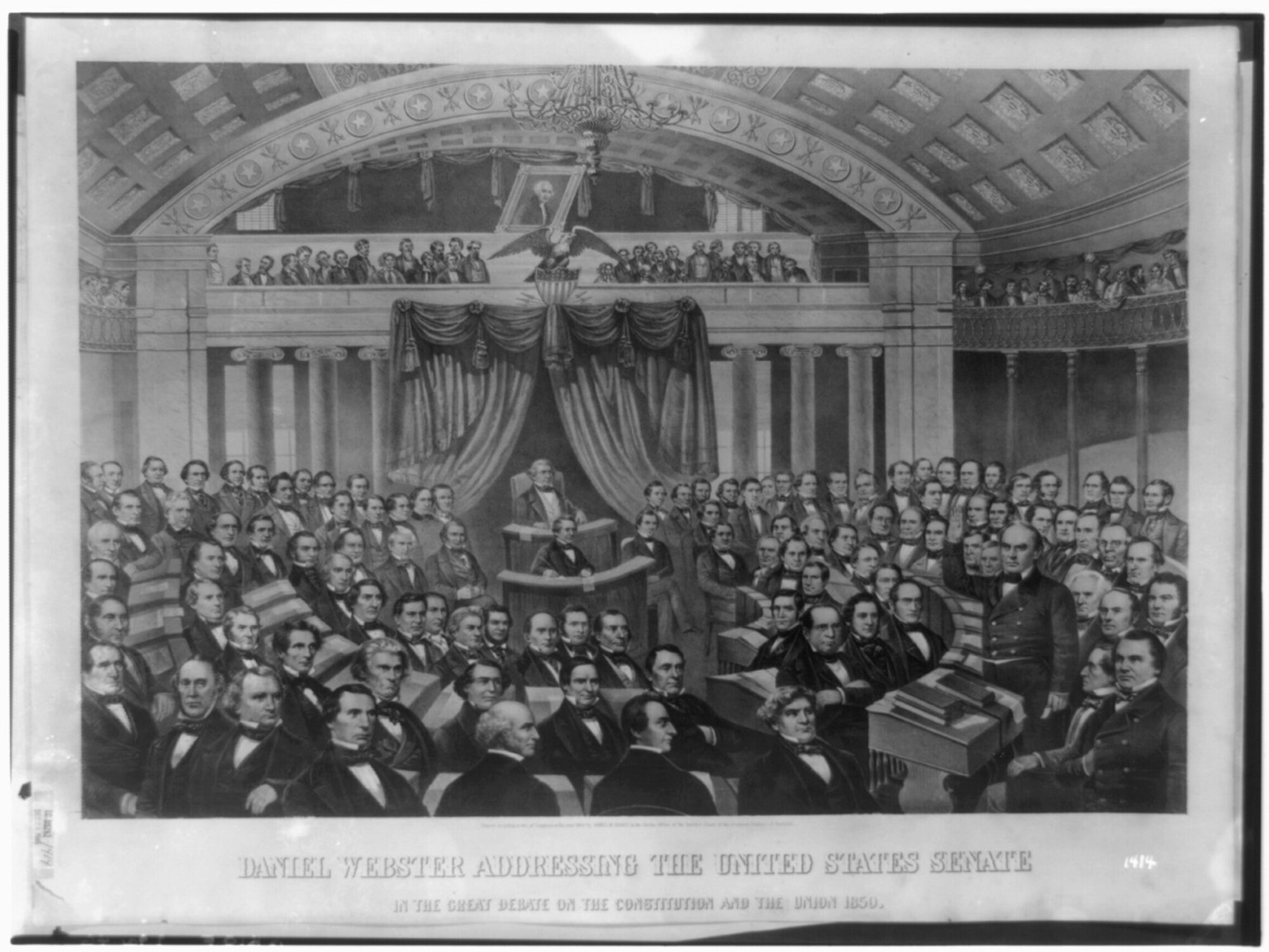

But Webster’s real stage was the Senate floor. In January 1830, he sparred with Robert Y. Hayne of South Carolina in what would ultimately be one of the signal debates in American history. Though ostensibly about western land policy, the clash quickly transformed into a philosophical brawl over the nature of the Union. Hayne, defending Southern interests, championed the doctrine of nullification—the idea that states could ignore federal laws that they decided were unconstitutional. He depicted the federal government as a creeping tyrant, while the North was simply economically exploitative.

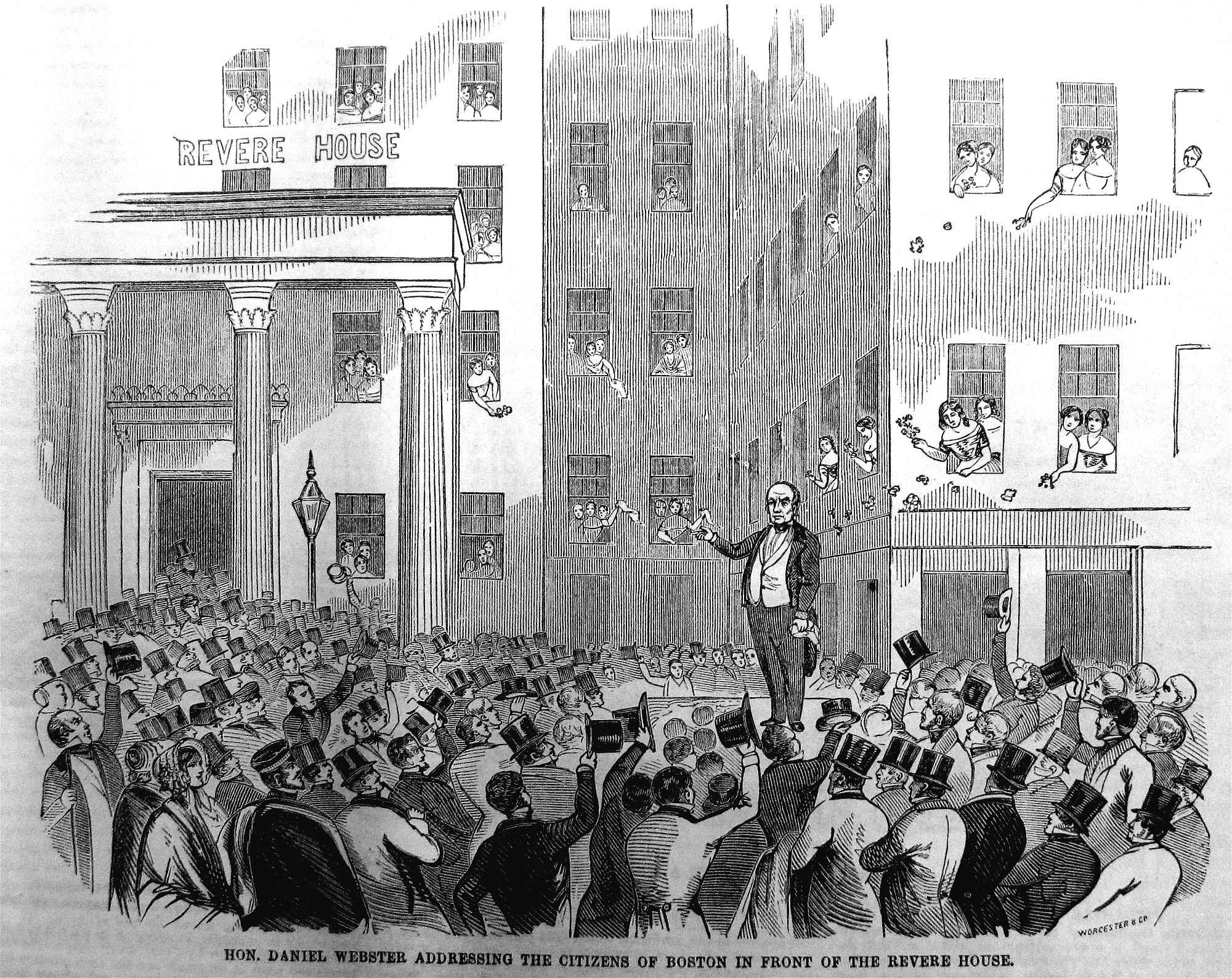

Webster’s rejoinder was thunderous. He dismissed nullification as a “political absurdity,” stating that the Constitution was not a compact among states but a contract with the people. He raised his voice in defence of national unity to a point where he delivered line that would be burned into the American memory: “Liberty and Union, now and forever, one and inseparable.” The hall fell silent. Even the opposition acknowledged the rhetorical genius of the moment. It would become more than a counter-argument – it would redefine Americans.

via Shutterstock

Webster had an extensive political career with several parties. He served in the House as a Representative from New Hampshire and, later, from Massachusetts. He also served multiple terms as a Senator from Massachusetts. As Secretary of State under presidents William Henry Harrison, John Tyler, and Millard Fillmore, he brought America into a new phase with the Webster–Ashburton Treaty, ending frictions with Great Britain, especially over the Maine–Canada border. But in Webster’s waning years, there was plenty of compromise and infamy. His support of the Compromise of 1850, in part to save the Union from increasing sectional discord, cost Webster his standing with abolitionists.

Though morally conflicted, Webster believed the Union’s survival was paramount. His stance reflected a tragic tension between conviction and necessity, a dilemma that haunted many antebellum leaders.

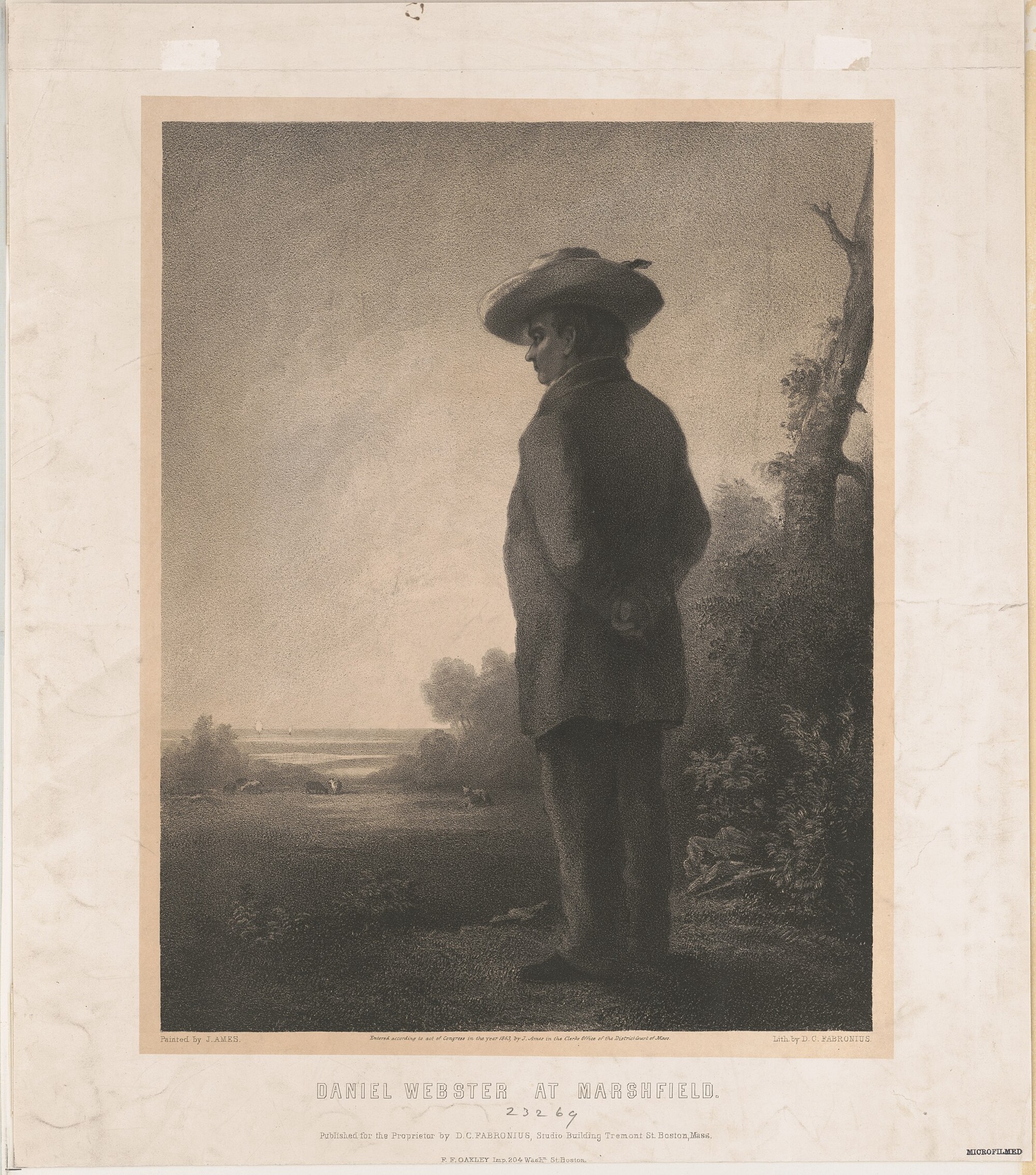

He died in 1852 at his Marshfield estate, leaving behind a legacy of legal brilliance, rhetorical mastery, and constitutional nationalism. Alongside Henry Clay and John C. Calhoun, he formed the “Great Triumvirate” of antebellum politics. But unlike his counterparts, Webster’s legacy rests not in legislation, but in language—in the thunder of his speeches, the architecture of his arguments, and the enduring idea that the Union was not born of convenience, but of conviction.

Leave a Reply